Julian Stallabrass'ın 11 Kasım 2017 günü Artist-2017 Ütopya Sergisi kapsamında, Uluslararası Eleştirmenler Derneği-Türkiye'nin davetiyle yaptığı konuşmanın metnidir. Metnin Türkçe çevirisi önümüzdeki günlerde yayınlanacaktır.

The art world, especially during its few boom years up to 2008, and since the financial crisis, has been going through some very strange times.

There has been a deep split between:

Documentary, political engagement and war on terror

Relational aesthetics/ participatory work

And the noisiest tendency: spectacular, marketised art for elite

Now, this could be a peaceful divergence—we could imagine that the different kinds of art may inhabit their own discrete environments without disturbing each other—as new media art did with the mainstream art world for so long.

But it hasn’t been like that, and it’s particularly the strange schizophrenia between the political and the super-rich art I want to look at, and its consequences for theory, critique and the engagement of the art world with other realms and vice versa.

One place to start looking is in a parallel opposition with the kinds of things that are said about criticism:

--that it’s dead/ powerless/ complicit with the market, or powerless in the face of it

--that it’s renewed/ radical/ diverse/ thriving

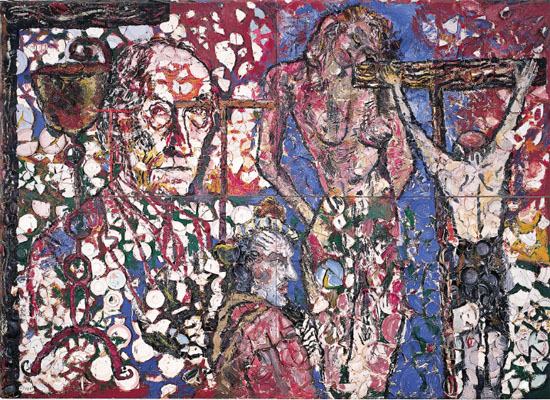

The first complaint is an old one, but it gained particular currency in the US with the waning of abstract expressionism and the idea of the Hegelian terminus for an autonomous art and with it of the influence of Clement Greenberg—a criticism that defines a field of art and directs it. The rise of neo-expressionism seemed to be a certain death knell for criticism: Julian Schnabel is the archetypal case here, since no significant critic seemed to support Schnabel but that didn’t stop him from becoming hugely successful commercially.

Schnabel, Painting Without Mercy, 1981

Damien Hirst, “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable”, Venice 2017.

So criticism, the story went, lost its position of previous dominance, and it did so in a welter of money and vulgarity, as Greenberg’s ‘umbilical cord of gold’ became something else entirely—a solid gold baby since raised to maturity, perhaps.

The current turn takes this to greater extremes than did neo-expressionism: the speculative contemporary art boom of the early to mid 2000s saw the rise of a great deal of populist art, and the strange post-Crash economic era did not much alter it, at least at the highest end.

So what is Populist art?

-- an art of simple character, generally figurative and expressive—or faux-expressive

--which has an enthusiastic engagement with commercial mass culture

-- delivered through branded artistic persona: re populist leaders/ Hirst as demagogue.[1]

--and (like populist politics) an art with wide popular appeal, made for the ‘people’, claim its makers, not to the art-world gatekeepers

In the US, most of the best-selling artists make very accessible work; and some (as in a backwash from the current popularity of street art) are associated with its first flush of success—Michel Basquiat, and George Condo (a branded painter of celebrities who has collaborated with Kanye West).

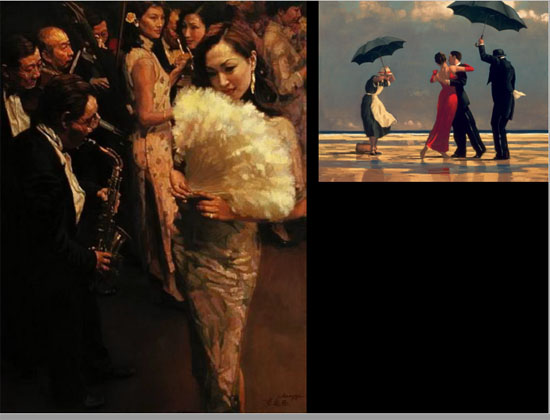

This development is also much fuelled by Chinese artists—now running neck-and-neck with the US in auction sales turnover for contemporary art—figure painters with branded styles, for the most part, and deeply conservative subject matter. Some of them such as Chen Yifei offer nostalgic visions of old wealth and the women who service it—worthy of our own Jack Vettriano.

And this growth and popularity are no illusion: think of Hirst’s Tate show (2012), the most successful monographic show ever held there; and remember the massive growth of the contemporary art world in economic terms—a near 10% p.a. since 2000, so that it has grown about 14 times bigger in the years to 2016.[2]

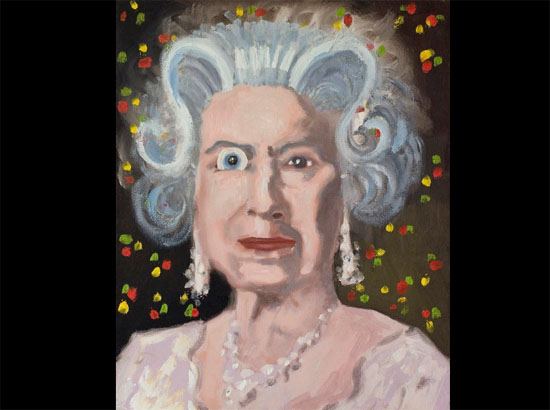

George Condo, “Insane Queen”

Chen Yifei

Damien Hirst, Tate exhibition, 2012

There are three big moves behind this populism:

--first, cosmopolitanism, and the sundering of national traditions, art-historical knowledge (the comparative cheapness of old art)

--the changing profile of collecting itself, as new buyers swept into the apparently profitable investment opportunity held out by contemporary art; many knew little about art history and bought on the power of famous names, readily identifiable trends and fashionable national schools—the latter were seen as marketing devices, not links to tradition, in which a mediatised and branded national identity is performed.

-- second, the growth of the new rich (their numbers and wealth), who want quick, easy, showy, branded art—they are money-rich but time poor. The art world, which has outgrown its once small and enclosed Euro-American domain, is less insulated than it was from the wider culture, having become a global social club for the mega-rich (Andrea Fraser’s 0.01%)—among whom are numbered, of course, the entrepreneurs of the great global media conglomerates. Their attachment is more to transnational and cosmopolitan culture than to particular national traditions, and is also strongly informed by what is popular—i.e. what is commercially successful.

--third, the growth of asset prices in the long recession, as immense funds slosh around, and cannot be productively invested, so it is sunk in luxury goods. Investment in art does not necessarily carry a price, as it used to (until the boom of the early 2000s, you were always better off putting money into stocks and shares than buying art) so that very expensive art is of a piece with buying similarly expensive houses and estates, yachts, antiques, fine wines, diamonds, etc.

Alexander Kosolapov, Hero, Leader, God, 2007, as shown at Saatchi

The official opening ceremony of the Azerbaijani pavilion of the Venice Biennale, 2013

Dakis Joannous’ yacht, Guilty, designed by Jeff Koons and Ivana Porfiri, 2013: Dakis Joannous = Greek-Cypriot industrialist and contemporary art collector

In my book Art Incorporated, I looked at growing threats to art’s autonomy, to the protected realm that makes it different from the general run of commercial culture, and saw them in state and business interference. Less so, in the power of the billionaire collector/ dealer/ private museum owner, I have to say—but their power is now obvious and over-weening. This could, one might think, be a way in which the autonomy of arts are protected, as with the patrons of many past eras: were are faced with the strange puzzle that the global elite (so separate from everyone else in their life experiences) seem to want to collect widely popular art. This is a fascinating development, and much to do with social media: the move of the elite, in business and otherwise, from determining to merely framing (and attempting to manipulate) popular taste.

This art does little to foster critical discourse—quite the opposite. That is partly a function of the kind of people it attracts: Charles Saatchi, of all people, mounted an assault on dealers and collectors as vulgar and self-regarding. And influential US critic, Dave Hickey, noisily announced his retirement from writing criticism, in disgust. Art is now too popular (‘I miss being an elitist and not having to talk to idiots’, Hickey says in a recent interview); art is made for a bunch of extremely rich folk, for whom the critic acts as courtier or ‘intellectual headwaiter’. Or Ivor Braka, a London dealer since 1978: “The art market has become an excuse for banking in public. People are displaying wealth in the most ostentatious way possible. It’s luxury goods shopping gone wild.”[3]

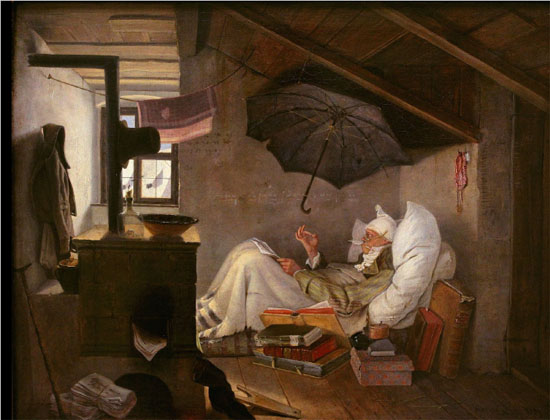

Carl Spitzweg, The Poor Poet, 1839

Plainly, we are far, far away from the old foundations of autonomy and social distinction: Bourdieu re avant-garde art which had almost no market:

The world of art, a sacred island systematically and ostentatiously opposed to the profane world of production, a sanctuary for gratuitous, disinterested activity in a world given over to money and self-interest.[4]

But beyond that, as Chris Dercon (once director of Tate Modern) claimed in a talk about soft power, the very expense of the art flattens the range of available things to say about it. It can’t be criticised because it’s too valuable! Remember that the asset price of an art work is merely a bet, it relies on a belief system. Attempt to puncture it at your peril. The newspaper critics become reduced to agents of PR, for the art, their papers and for themselves: think of Jonathan Jones at the Guardian, a figure who transparently and cynically writes provocations as click-bait.

A recent (2014) issue of the Brooklyn Rail carried many features about art criticism across Europe (under auspices of AICA): despite very diverse circumstances, and accounts from nations with long-established art worlds and those adjusting to the end of dictatorships (from Spain to Romania), similar patterns emerge: of a rapidly growing art world, with a mix of public and private institutions, engaging much larger audiences; and simultaneously of an embattled or even failing art criticism, withering in the demand for servile publicity.

In part, this reflects much of what James Elkins had to say about art criticism in his 2008 survey: there was a lot of it, it was mostly tied to publicity in vehicles like the exhibition catalogue and the magazine review (tied to advertising), it was not much read, and it was rarely the subject of wider comment.[5]

Some factors bearing down on art criticism apply to the decline of print journalism as a whole: time and resource constraints which mean that press releases get passed little altered into the press—due to profit gouging and the failing of the print model as its advertising declines, especially since the financial crisis. And some are specific to art criticism: as we have seen, that an art world fixed on investment value has little use for critique.

To take one striking example from the Brooklyn Rail survey—that of Denmark: it has seen the rise of many respected and widely seen artists with a global reputation over the last 20 years—including Tal R, Olafur Eliassion, Superflex, Elmgreen and Dragset—yet with almost no coverage in the mass media, and none on TV. There remained (in 2014) only one full-time newspaper critic in the entire country.[6]

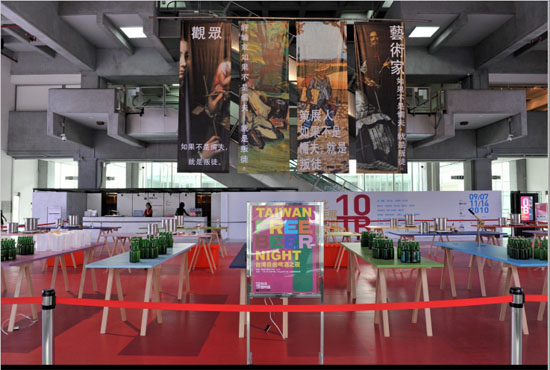

Superflex, Free Beer, Taipei Biennial, 2008.

So, to move away from the most marketised art to briefly touch on the other world, that of the biennial:

--political art, an art of crisis with often pedagogic and radical content, often Brechtian in mode—and its content stages a series of negations since it is anti-nationalist, anti-religious, anti-neoliberal, anti-sexist and anti-racist; and so it offers at least implicitly a series of positive ideals. The 2015 Okwui Enwezor curated Venice Biennale is a great example, as is the 2017 Documenta.

--in form, it generally favours the documentary with video, film and photography, or political collage and installation, or performance, much of it not very marketable

--especially since the start of the financial crisis, it has been increasingly explicit in its political engagement, particularly with Occupy (Berlin, 2012, curated by Artur Zmijewski and Joanna Warsza) and the new social movements generally

Occupy Berlin, 2012

What kind of criticism does this world foster? Under the impact of the wars on ‘terror’ and then the financial crisis and its still unfolding recession, this is surely richer than for many years:

There are first the artist-theorists, some of them veterans, plunged into new relevance and popularity after decades in the neoliberal desert (like Jeremy Corbyn): Martha Rosler, the late Allan Sekula, Victor Burgin, and those of younger generations—Coco Fusco, Broomberg and Chanarin, Hito Steyerl—in many cases, their critical writing some of the sharpest and most perceptive around.

Then there are the philosophers and other theorists who are called on to engage with the art world, and do so extensively: Judith Butler, Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, Donna Haraway, Agamben, Latour, Badiou, Groys, Ranciere, Zizek, Peter Osborne, Saskia Sassen, Paul Virno…one could go on...

Allan Sekula, Shipwreck and Workers, 2005, Documenta

And new generations of critic-theorists, who have a considerable intellectual hinterland, and are not the slaves of the (reduced and spectral) newspapers: people such as Claire Bishop, Isabel Graw, Ariella Azoulay, Eyal Weizman, McKenzie Wark, Nina Power, among many others.

And in all this, there is much new thinking on new economic models and automation, labour, on the place of cultural work in society as a whole, feminism and gender identity, ecology and decolonising thought... Alongside this, there has been a marked resurgence of Marxist cultural thinking, along with its thought generally—in HM, New Left Review, Jacobin, N+1, etc.

This strand was very present at Venice in 2015, both theoretically and in artistic terms: Alexander Kluge and Isaac Julien addressed Marx directly. Capital was read each day in the central auditorium of the Italian Pavilion. And Marx is listed as an artist in the catalogue!

Isaac Julien, Capital, as shown at Venice, 2015

So, to go back to the division with which we began, on one side:

--spectacular, branded, usually painted work for decorating billionaire’s museums and living rooms, a creature of public relations and social media popularity

On the other:

--a politically engaged, radical art centred on documentary, and defended and informed, enacting and engaging with some quite difficult theory

Yet, in some senses, they are not separate, but feed off each other: the biennial business and the art fair are wings of the same dove (as Joseph Backstein, the director of the Moscow Biennial incautiously commented on its founding in 2003). Among the common elements:

--the occasion and the event; some aspects of Frieze also applies to Venice, for example: the flocks of collectors arriving in private jets, the parties, and the intricate circles of ranked privilege and admission.

--that the money of the one world bears up some of the activities of the other; and that the biennial is often mounted for economic reasons of regional development, tourism, fostering of the local commercial art world, and is of course a way to raise reputations and prices.

--that all art has been influenced by the increased speed of cultural cycles (an interest of David Harvey’s, of course): to become easier, more accessible, quicker and glossier: think of the development of video.

--both are creatures, increasingly, of social media feedback: as was very clear in the 2017 Venice with the hit of the biennale, Imhoff’s Faust and its model-performers—in a work that allied critical acclaim, mass media attention and a vast amount social media sharing which was taken as an integral part of the performance.

And at the extreme of the association of these two worlds, there is a perverse paradox: collectors who buy works that depict political catastrophe. This is particularly so of large-scale photography, which comes close to being used as the new history painting. Many conservative aesthetes moaned that the 2015 Venice was too gloomy, metaphorically and actually dark and too overtly political, but there are scenes of political and ecological catastrophe that sell. Think of Sebastião Salgado, or Richard Mosse or Edward Burtynsky:

Why do photographs showing disaster hang in the rooms of the art-buying elite? A portion of the rich choose to live with big prints, matching the scale of postwar painting, which bear dire images of war, poverty and environmental destruction. They are usually technically accomplished, carefully composed and finely printed. Disaster, writ small or large, a single person’s grief or the destruction of a city, finds its home in beauty and in beautiful homes. What species of social distinction is gained by owning and displaying such objects, and what pleasure is found in looking at them?

Burtynsky, Oil Spill #2, 2010

Burtynsky, Oil Bunkering #1, Niger Delta, Nigeria 2016

In Edward Burtynsky’s work, the contradictions of this genre of art photography are forced into piercing proximity. In his well-known major project about oil, over a decade in the making, that engine of industry and consumerism is represented in large, striking images which indicate the sheer vastness and filth of the enterprise from extraction to exhaust pipe. Most people experience the oil industry from the consumer end: the endless growl, sigh and drone of aerial and ground traffic, the pollution of our every breath, the threat of speeding vehicles that drives social life from the streets, and the stench of the petrol station. What is hidden from those who do not live in oil-producing areas is the Stygian filth of the extraction process, and the vast destruction of land and life that it causes. Here the scale of the prints has a point that goes beyond art-world convention, as the extent of oil’s ruination of land, sea and air finds metaphorical expression in the way the viewer’s body is dwarfed by the size of the works.

So the fundamental move here is something close to political propaganda: the use of the highest technical capacity of photography, a central medium of consumer ‘publicity’, to render dark images of the consequences of consumerism. The viewers’ implication in the system of destruction, known to everyone but pushed to the back of the mind, is forced upon us: that a petrol-driven trip to the shops to buy bits of plastic causes the tar-sand mining of Canadian wilderness.

Even so, the gallery viewer may take pause, while contemplating these sublime spectacles of environmental degradation, to reflect on the objects in which they inhere. The photographic image is now, after all (and especially for Burtynsky since he moved to using digital cameras for his aerial work in the ‘Water’ series), a virtually weightless data file—the values read from an array of photons processed to make an ordered sequence of electrons. The prints, though, are large, heavy and rare (they are made in small editions); they are luxury items to be guarded and carefully presented by curators for the public, and conserved carefully by the few able to own them privately. They are flown from venue to venue, art fair to art fair, for the consumption and contemplation of the small elite that buys such art and the larger one that views it.

Mosse, Infra

This is equally true of Mosse, and his extraordinarily large and technically polished prints, made using an old infrared surveillance film; here geared to the Congo conflict, and to coltan and diamonds, the former a product that implicates every mobile phone user.

In both, sublime spectacle. While in the modernist era, the vastness of industry was often taken as the magnification of human powers that would lead to mass emancipation, now they are more likely to be read as apocalyptic pronouncements on the limited capacity of the global environment to sustain mass consumerism. The sublime still operates in Burtynsky’s pictures, because the viewer is protected from the threat, insulated from the stench of industry and industrialised agriculture, from the poisons that cling to skin and work their way into the bronchial tree; and protected, also, from too harsh an experience of chaotic filth by compositional order within the frame. Yet the real dangers of flood, drought, hurricane, heat wave and earthquake remain, and beyond even those perils, the prospect of an environmental collapse devastating enough to bring down the social order. It has, after all, happened many times before.[7] From that disaster—and that of state collapse in the Mosse—not even the global elite would be safe. So the sublime is there, but it is no longer quite intact as the enjoyment of a horror held at a safe distance, but is infected by the growing threat of mass extermination.[8]

Burtynsky has often said that his pictures enact the contradiction of environmental conscience and consumerism.[9] Consumers seem to be caught firmly in the bonds of guilt and desire, and the allure of a Burtynsky print brings into view the tangled net of the two emotions, as viewers admire and consume the image of their own destruction. Burtynsky’s pictures may also enact the powerlessness of conscience in this capitalist crisis.

How do they call to the viewer? To enjoy, in a typical art-world convention, the frisson of inescapable contradiction? The concerns of the work seem too serious, too deadly, for this. To admire the linked impact of their extraordinary craft and their propaganda value? As an invitation to greater awareness and morality? To share them digitally so as to magnify their effect? To campaign for green issues and the protection of the wild? Or do they call to the viewer as commodities? Their technical accomplishment and compositional order may induce the collector to make a purchase. There may be many motives for buying: perhaps the work will be widely shown, shared or even given away to a public institution. Yet if the intention is to keep the print as a private treasure, or to take it as a pure investment—to do that, on our present circumstances, would be an act of strange perversity.

You may wonder why I have undertaken this long digression on Burtynsky: well, I was commissioned to write an essay for a catalogue for the artist, I wrote something along these lines, and (it may not surprise you) it remains unpublished. There are many acts of censorship—I’ve experienced a few myself—which generally go unremarked and unpublicised. The decline of critique is partly, then, a matter of time, asset values and PR; but also of active repression.

Salgado, Kuwait, 1991

And again, such images are not just popular with collectors but have a mass audience. Sometimes they bring out an interpretive position that you would more often associate with populist art. I participated in a panel following a showing of Wim Wenders’ film on Salgado, Salt of the Earth: while we all offered critique from a fundamentally supportive viewpoint, the audience responded badly, in a mode worthy of Bruno Latour’s writings on the ‘post-critical’: Salgado does his own thing, he’s passionately committed to it, and it’s mean to criticise!

So, in this strange compact of commercialised disaster pictures, is there a place for critique? And is there a critical equivalent to the cross-over between populist and biennial art?

Billionaire’s living room: Steven Cohen’s New York apartment

The first thing to say is that the contemporary art world has become much more like a regular business than it used to be—remember its colossal expansion in the last fifteen years, and its mass of new collectors, who often buy for instrumental purposes of overt self-display and investment value. And the business, one based on faith (like the value of money or shares), needs propaganda to support it.

The vast increase in quantity bears on quality: the number of contemporary art museums (among others), essential tools in gentrification and regional development, grows rapidly across the globe, making the museum and art experience a more common part of everyday life. 700 new museums (of all categories) are opening around the world every year. More museums were built between 2000 and 2014 than during the previous 200 years.[10]

Here Fredric Jameson’s demand that we dialectically see the positive as negative may be put into place:[11] the over-population of arty products and places to show them may serve the salutary demands of demystification.

Frieze Art Fair, New York

All this puts pressure on an elite culture that has long served as a mask for neoliberalism (the capitalist status quo), while the economic system itself spirals into crisis. So the first mask to slip is that of quantity: the sheer size of the contemporary art world.

Sylvère Lotringer, in a long discussion with Paul Virilio complains of there being simply too much art, and consequently:

Art has become a sort of black hole. The pull, the glamour, the giddiness of it all is too strong for anyone to resist. And at the same time, it’s just crude business deals and shady calculation. It’s become no different than anything else.[12]

Thus its necessary integration into the everyday life of PR and the mass media, and its consumption (at least at a distance or through exhibitions) by a much larger, educated, global middle class—more leisured but also more insecure.

We know, too, that value and criticism are linked from the Richard Prince hedge fund campaign (as researched by a student of mine, Molly Concannon). Investors were seeking ‘undervalued’ artists: one way of knowing that Prince was undervalued was because of the mismatch between auction prices and reputational value, which including writing. In a marked success, this campaign drove up his prices from the few-thousand dollar mark that they had maintained for decades to make Prince one of the most expensive artists on the planet.

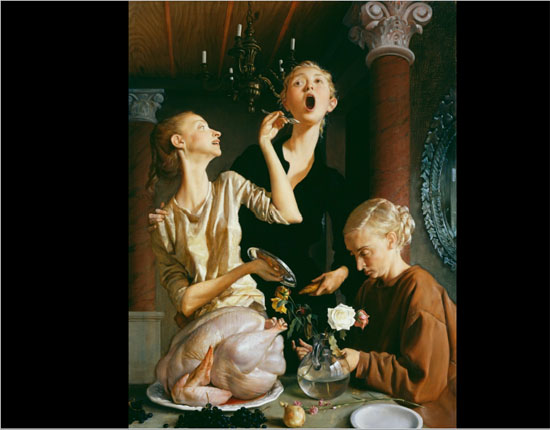

Or think of John Currin, who is hugely successful commercially but whose dealers have had to buy in heavyweight ‘critical’ writers to try to correct an embarrassing imbalance between gilded market price and a paucity of art literature.[13]

Richard Prince, Cowboy

Currin, Thanksgiving, 2003, Tate

So there is indeed an equivalent criticism of the meeting point, especially in the monographic catalogue essay for living artists, for which quite large fees are paid, and where the veneer of critique meets public relations. I won’t name names here, but we all know of the fundamentally propagandistic and positive essay writing, in which a parade of theoretical greats are found in some loose or unspecified way to validate a set of artistic commodities.

There are definite rules to such essays: they need to offer critical distinction, which makes for a cramped and difficult style. The right sort of names and concepts should be invoked and the occasional paradox spun—on occasion, using some of those philosophers I named earlier. And they must, above all, be affirmative.

But if criticism is a product just as much as the work of art, then some of the same questions about quality and quantity can be asked of it; and it is subject to the same forces of glut, precipitate growth and rapid acceleration.

Alexandre Masino, The Instant Art Criticism Phrase Generator, 2010

So if difficulty and paradox are markers of distinction, we would expect to find them deployed for their own sake—and we do, frequently in art’s promotional literature, and even in theoretical literature generally. This is very much a peacock operation: the display of fitness through a display so extravagant and costly that it becomes a handicap—for writer and reader alike, and for the development of clear, radical understanding. Think here of almost all of the literature of curating…

But this operation is in tension with the demands of industry, and its need for ever greater speed and extent of production—of the jobbing academic who knocks out a dozen ‘theoretical’ catalogue essays a year, each for a fat fee: the thinning and spreading in populism applies to criticism too.

The old image of the intellectual and of slow and sustained thought over decades is surely under great pressure in this industry—Adorno would be one model here, who says that speedy thought is that done with a pencil in hand.

We may contrast Martha Rosler and her tortured Facebook post from a few years ago: ‘I should be writing. I want to be writing. I mean to be writing. Therefore, I am on here on FB instead. [kill me now]’ There may be something interesting going on here, in which once again the negative may contain a positive.

Rosler, Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975

Rosler’s artistic work has always been fast and cheap; and this was part of its principle: a feminist and leftist rejection of traditional quality. Her writing, in contrast, has been sustained, rigorous and polished. But now she is always on Facebook: and who is to say that her insistent posting—quick, short, regular, provocative—with thousands of followers (just short of 5000) does not have a greater effect than her books of essays?

What is more, with the erosion of the distinction between those who make and those who merely consume in social media, there emerges an integral understanding of complex cultural matters. We see this very clearly in the much greater understanding of how photography can be manipulated, and is used to produce particular effects. This used to be the stuff of brow-creasing postmodern theory but many people hardly need this education anymore: it is informally ‘taught’ by Instagram and Photoshop. In this, of course, the figure of the artist, the curator and the critic become hybridised and begin to dissolve: another striking aspect of the Brooklyn Rail issue was the extent to which critic was just one job among many: artist, teacher, curator, administrator, consultant...

It used to be a common complaint on the left: everything is commodified! Even our dissent! But more often heard now is the point that it works both ways: commodification alters and arguably pollutes dissent, but dissent also alters and pollutes the commodity, using its power to spread slogans, jokes, campaigns and actions that corporations and states would rather not be heard—and especially now that the capitalist system is in such evident and prolonged crisis and drift.

Steyerl sees this clearly in her art works, with their parodic take on the corporate propaganda video to produce an entertaining, funny, glossy, high-production value Brechtianism. And likewise in her writing, which allies scholarly references with accessible provocations (she is not alone here—Slavoj Žižek and Boris Groys come to mind).

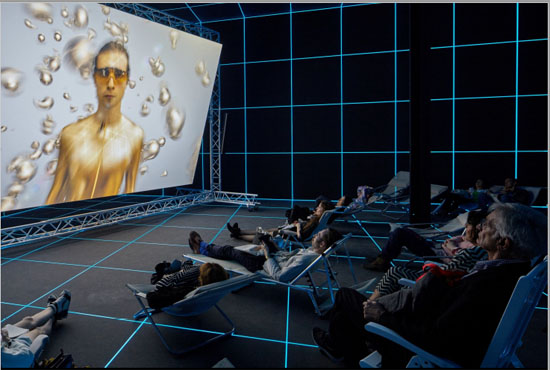

Steyerl, Factory of the Sun, 2015

So perhaps, as pressure is put on the old forms of aesthetic distinction, so they bear too on critical distinction—and that we should welcome the demystifying effects in both: that the impetus of the cheap, the fast and the popular holds as more potential for change than the pricey, the slow and the elite. But I should admit: I have just spent ten years writing a book, which has a section on speed and slowness, and the resources of the poor in slow acts of erosion to defeat the rich and the well-equipped. We should not forget, either, the old mole who slowly burrows and undermines. So it may be that we lay the old over the new, explore relations between them, and pursue both. They have the guns but we have the numbers, an old slogan goes—and we may add, we have time too.

[1] See Francisco Panizza, ed., Populism and the Mirror of Democracy, Verso, London 2005, pp. 24-6. [ch page refs]

[3] Quoted in Scott Reyburn, ‘Can an Economist’s Theory Apply to Art?’, New York Times, 20 April 2014.

[4] Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production, ed. Randal Johnson, Columbia University Press, New York 1993, p. 197.

[5] James Elkins, ed., The State of Art Criticism, Routledge, London 2008.

[7] There is a large literature on the connection between the collapse of complex societies and environmental degradation. See, for example, Jared Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, Viking, New York 2004. There is some evidence that global warming may lead to increased tectonic activity. See ‘IPCC Studies Link Between Warming and Earthquake Activity’, New Scientist, 5 October 2011.

[8] See Jean-François Lyotard, ‘The Sublime and the Avant-Garde’, in The Inhuman, Polity Press, trans. Lisa Liebmann, Geoffrey Bennington and Marian Hobson, Cambridge 1991.

[9] See, for instance, Jonathan Blaustein, ‘Edward Burtynsky Interview’, APhotoEditor, 25 July 2012.

[11] Fredric Jameson, Valences of the Dialectic, Verso, London 2009, pp. 427f.

[12] Sylvère Lotringer/ Paul Virilio, The Accident of Art, trans. Michael Taormina, Semiotext(e), New York 2005, pp. 86, 65.